Haleh Mir Miri, dancer

Becoming Body

Haleh Mir Miri is a graduate student in Women, Gender and Sexualities Studies at the University of Saskatchewan. She also holds a master's degree from the University of Science and Culture in Iran. She has continuously been an active member of women and gender communities over the past ten years in Iran, concerned about women's conditions. She was a member of the Million Signatures Campaign to Change the Discriminatory Laws by Iranian women. Simultaneously, she was an author for an underground Marxist-feminist periodical covering women's issues distributed in Tehran and other provinces.

Haleh Mir Miri is a graduate student in Women, Gender and Sexualities Studies at the University of Saskatchewan. She also holds a master's degree from the University of Science and Culture in Iran. She has continuously been an active member of women and gender communities over the past ten years in Iran, concerned about women's conditions. She was a member of the Million Signatures Campaign to Change the Discriminatory Laws by Iranian women. Simultaneously, she was an author for an underground Marxist-feminist periodical covering women's issues distributed in Tehran and other provinces.

I remember those days when I was a plump woman, thinking about getting rid of twenty-two pounds every day. I wanted to lose this weight once forever. Then, while I was working out in the gym one day, I came across to attend an Iranian dancing class that was available. Then I found myself in the world of dancing. My world, simultaneously divided into two parts: "subjectivity/mind and embodiment." I noticed that the act of understanding is not down to the subjectivity or mind only, but the "body" in its own turn has a kind of memory and agency.

The first dance class, which I attended, was a national-Iranian dance class. The National dance style consists of some classical ballet techniques combined with the Iranian folklore movement. Simultaneously, it was a seductive, feminine style of dancing that did not fit with my gender-sensitive state of mind but intriguing and stimulating. I began dancing with girls and women whose painted lips and bizarre clothing, along with their looks full of femininity, intermingled with each other, heating the class, which was an underground sports club reeked of damp. The music we used to dance with was mainly traditional, famous, or folklore. We primarily were told to imagine a male figure before ourselves who was willing to pay a great deal of attention to us. In this way, the National-Iranian style of dancing to me, depending upon the cultural factors by which Iranian women's bodies had been grown-up, reproduced the feminine bodies I was not too fond of.

Then I commenced asking a set of questions about what dancing is. I employed dancing to dig into the times past to explore my body's permanent motions by which I had been growing up. In my body's history, I saw a girl who was prone to remain motionless and isolated, a girl reluctant to perform different motions. I had not chosen this frozen state of sitting motionless with no exhilaration willingly. On the contrary, social structures, such as the family, school leading me to this position. However, those questions about dance's nature remained in my mind.

The vast difference between how I was experiencing my subjectivity and the style of dancing I was practicing made me leave the dancing ground I had become highly interested in. Then, I began to think about other dance styles. As dancing has been banned in Iran for more than thirty years after the Islamic revolution, dancers perform in different private spots or theatre rehearsal spaces. Then I found some of these milieus on social media, where dancers used to advertise their classes hiddenly.

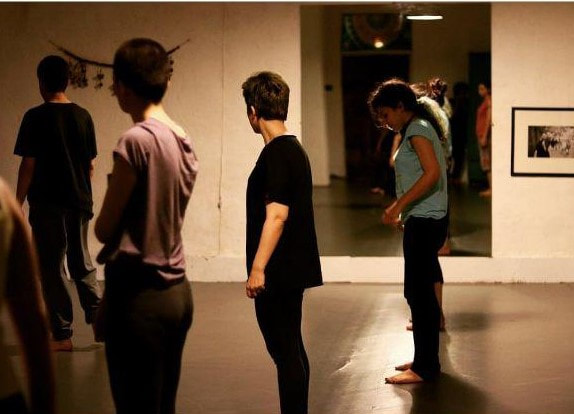

I attended a new dance class, which was utterly different in dancing techniques and style. It comprised of boys and girls, a not conventional feature in dance classes in Iran. The participants in this class, who were primarily not professional dancers, considered the body a sensual source of knowledge, attempting to discover their bodies and senses again. They were trying to remember those feelings in their bodies, oppressed by the power structures and social domains over time. What I noticed in these classes, however, was that the women had more challenges with their bodies as if they confronted with their oppressed bodies twice a time more than the men.

The vast difference between how I was experiencing my subjectivity and the style of dancing I was practicing made me leave the dancing ground I had become highly interested in. Then, I began to think about other dance styles. As dancing has been banned in Iran for more than thirty years after the Islamic revolution, dancers perform in different private spots or theatre rehearsal spaces. Then I found some of these milieus on social media, where dancers used to advertise their classes hiddenly.

I attended a new dance class, which was utterly different in dancing techniques and style. It comprised of boys and girls, a not conventional feature in dance classes in Iran. The participants in this class, who were primarily not professional dancers, considered the body a sensual source of knowledge, attempting to discover their bodies and senses again. They were trying to remember those feelings in their bodies, oppressed by the power structures and social domains over time. What I noticed in these classes, however, was that the women had more challenges with their bodies as if they confronted with their oppressed bodies twice a time more than the men.

Thus, I started a new bodily journey within my body, movements, sexuality, and praxis. I wanted to create a new body that could convey what it had inwardly; a body that could speak its organs' memories, the history of head, hair, chest, tights, etc. Well, I am in the middle of this process. Now, I understood that dancing creates a new entity with new specific capacities; I am currently in the middle of this process; I will always be in-between-ness of my body and its movements.